Bologna: not only Tortellini and Towers?

A Few Thoughts After Watching Clive Myrie’s Italian Road Trip

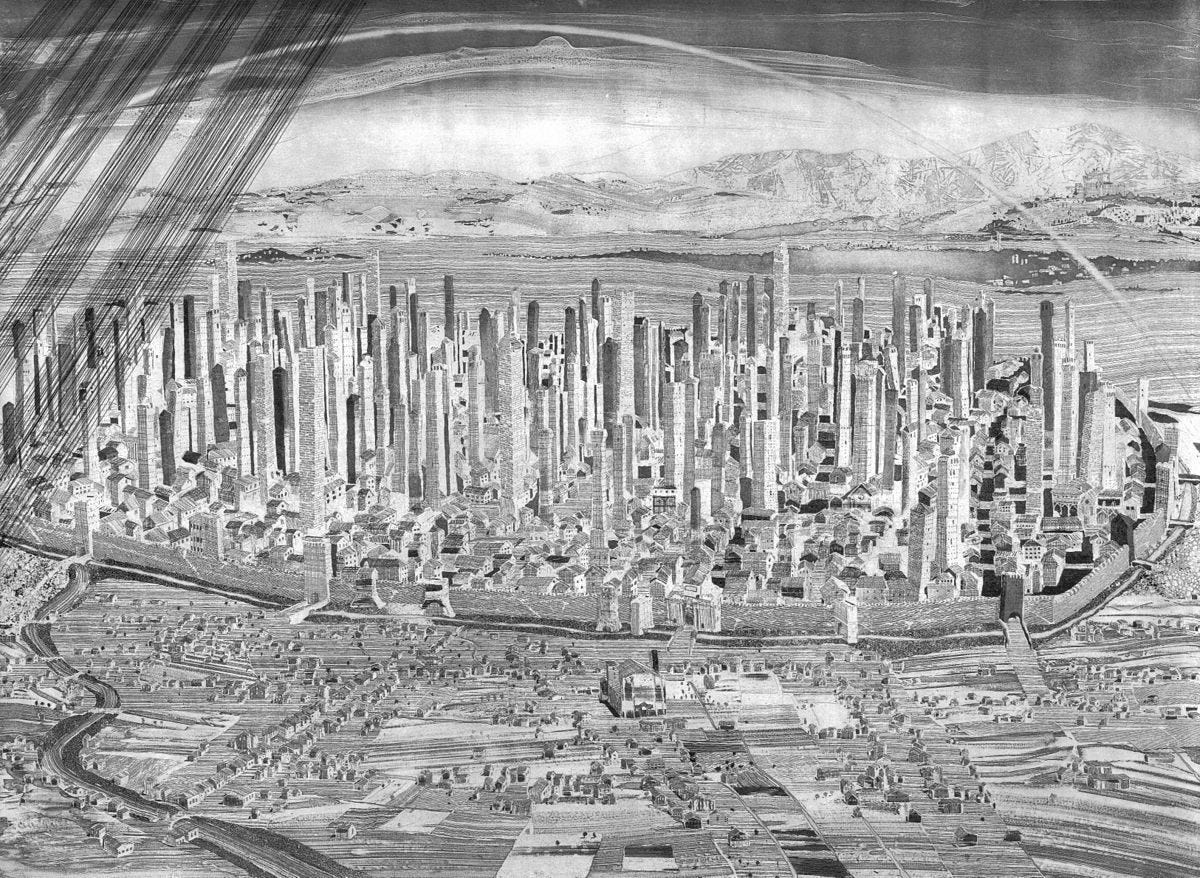

They say Bologna in the middle age was similar to an unlikely Manhattan of its time, so I would like to start with this image.

As many of my readers will know, my passion number one – together with plants and meteorology – is places. Since childhood, places have been for me an endless source of fascination, even before I could consciously be aware of it. I should have, somehow, made a career out of this passion – maybe as a geographer of sorts – but I didn’t, in much the same way that I didn’t train as a botanist and I haven’t made a career out of it. But it still holds true that plants and places are my main passions (the overarching passion for meteorology is another matter altogether, and I won’t deal with it this time), and as a matter of fact, plants and places have somehow turned into – if not an identifiable career – at least my profession. Working as a guide, for me, most of the time means precisely dealing with plants and places: and this is what I ‘profess’, not just in my work, but in my daily life, also. It is certain, however, that my passion for places hasn’t followed a straight line. This still isn’t an easy one for me to go about. But I do live out this passion in my own way, first of all by visiting places, writing about them – and watching lots of documentaries, both in Italian and in English. On places, that is. And frankly, not only do I enjoy watching documentaries, I’d love to make them, too – but that, also, is another story. For some reason, I especially enjoy watching British documentaries, maybe because they feed what I’ve identified might be my niche: being an insider and an outsider at once, in relation to, especially, Italy. Being an Italian-born man who writes in English about Italy offers quite a unique take on things, I’d say.

Be as it may, by pure chance (I don’t believe in chance, by the way), I happened to discover a recent series of short documentaries presented by a BBC1 news journalist, Clive Myrie. It is aptly called Clive Myrie’s Italian Road Trip, and it is comprised of fifteen episodes, some of which deal with the ‘usual’ suspects (Naples, Rome, Venice…) but some are set in lesser-known places, at least to non-Italians (Torre del Greco, Barga, Conegliano…). The BBC documentary style is notoriously slick and follows a rather predictable format: introduction, main part, wrapping up and quick anticipation of the following episode (dropped, in this case). These episodes are so short that it’s all stripped to the bone, and the flesh is what matters – which probably amounts to just over twenty minutes of content. So, for the time being, I have watched four episodes in this series, starting from: 1. Puglia and Basilicata (which is mostly focused on Matera); 2. Catania (in which the city is barely seen); 3. Palermo (with a substantial part on Mussomeli – one of the towns participating in the “house for a euro” scheme). But then I couldn’t resist and skipped to ... 12. Bologna. I’ll go back and watch the rest, but I couldn’t help the curiosity of viewing the episode on the city where I was born. It was an interesting watch, no doubt, and I will have to re-watch it.

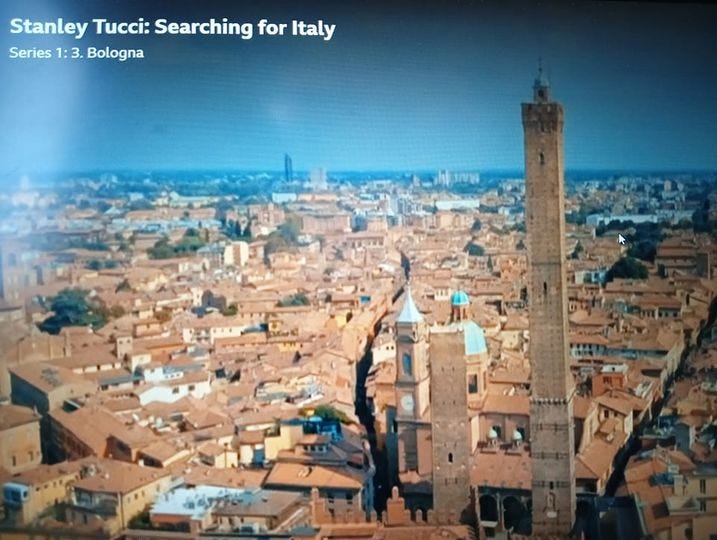

A still image from the Bologna episode of “Clive Myrie’s Italian Road Trip”; the top of the Asinelli tower is visible to the right.

This is the latest addition to a long list of documentaries I have already seen on Bologna over the years: I had watched a few times Rick Stein’s episode in the “long weekend” series (which was mostly on food – being Stein a cook). And I had watched a couple of times Stanley Tucci’s Emilia-Romagna (featuring a fair amount of Bologna in it, although not exclusively). But as a rule of thumb, it almost goes without saying that whenever Bologna features in a documentary – at least abroad – it’s almost invariably about the food (it is quite a different story, for example, if you watch the RAI’s documentary from the series called “Di là dal fiume tra gli alberi” – named after Hemingway’s book; there is a recent episode on Bologna in which food only plays a minimal part, as it’s mostly on people’s stories and social aspects of the city). But this latest documentary struck me as particularly ... I don’t want to say shallow, as it wasn’t, and was actually rather enjoyable to watch. But it only told one side of the story. No doubt, it showed “the dolce vita” of Bologna ‘la Grassa’ (“the Fat one” – for obvious reasons), with a passing mention of it being also ‘la Dotta’ (“the Learned one” – because of its old university) – and none of its being ‘la Rossa’ (“the Red one”, for perhaps less obvious reasons: the colour of its bricks and walls – and by extension, its traditional political penchant). But that was basically it.

A still image from Stanley Tucci’s “Searching for Italy’s” series. Here they are preparing ‘ragout’ (or ‘ragù’), but he is actually in Romagna.

Clive Myrie’s episode on Bologna all seemed to be about how much people enjoy life there, and how the city’s people are among “the happier in the country”. Which is hard to believe, if you were born there. Of course, there are things I miss about my hometown – but it’s mostly about people (and places) that are no longer there, and this sort of existential nostalgia could never feature in a documentary, for obvious reasons. As if I’m honest, I don’t really miss Bologna as a whole, and I also have a hard time recollecting it as a location where people, in my experience, were especially ‘happy’. Indeed, the city does have peculiarities of its own, which made it outstanding especially in the post war period, when it became a sort of social laboratory that the whole country was looking up to, thanks to the ‘enlightened’ Communist mayors of the 1950s and 1960s, but these aspects were never touched upon in the documentary in question. I’ll come back to this later.

Of course, if you don’t know the place, and go there for a long weekend, it’s a great place to be: all you need to do is jump on a Ryanair flight – or a BA flight if you want to travel more comfortably (but, incidentally, bear in mind that Bologna’s airport is rather poorly served by low-cost airline companies from the UK) – and just spend some relaxing time there. How could it be anything other than enjoyable? And that’s the whole point of the program, I suppose: to entice you there with the good things about the place. And Bologna, no doubt, offers many: you can go in and out of the many ‘osterie’, eat “al fresco” in the alleyways, hop on and off buses or bicycles, climb the Asinelli ‘leaning’ tower. Yeah, that’s all great – I won’t deny it. But as a native, I don’t fully buy it – and two points especially grate on my ears: 1. I can’t quite perceive the ‘happiness’ that many of the locals feel compelled to show as genuine, making it sound as if they were living in the belly button of the planet. Maybe they really believe it, which would be even more worrying. Don’t get me wrong: I have fond memories of Bologna – I have said it already. But personally, I don’t recall it as a particularly ‘happy’ place: I have known and lived in places that felt a lot ‘happier’ to me. But I also know that I’ve never really entertained a particularly serene relationship with my birthplace; if anything, a rather complicated one, for reasons that are beyond the scope of this writing. But there’s another important point to consider, and that is much more in line with what this documentary is trying to show: 2. even people who have always professed to love Bologna and have never left it – like my mother – now say that it’s sold her soul to tourism, and that has significantly altered the energy of the city. Many homes are turning into Air B&Bs, more and more people are visiting, and as this process continues, the distinctive nature of the place – the genius loci – is progressively lost. A destiny shared by many other cities: think of Venice. Think of Rome, or Florence – or Barcelona. Welcome to the club, Bologna.

Above: the opening scene of Stanley Tucci’s “Searching for Italy’s” episode on Bologna also inevitably features an image of the “Two Leaning Towers” (the tallest is the Asinelli).

Below: This other still image from the Bologna episode of “Clive Myrie’s Italian Road Trip” shows the truncated top of another Medieval tower, now turned into a B&B.

And so, in the documentary, we have the unavoidable tutorial on how to make the perfect tortellini and tortelloni, patiently run by the two pasta sisters that featured also in Rick Stein’s “long weekend” series (they were a tad younger there, but their passion seems unadulterated by time). This time, though, we didn’t get the story on the spaghetti bolognese – thank God (by now, you should know they don’t exist in Bologna). But we have the equally unavoidable ascent to a medieval tower, reminding the casual visitor that Bologna in the middle age was similar to an unlikely Manhattan – but at least it’s not the Asinelli, this time; rather, it is a private one, turned into a slick B&B by a considerate owner, and perfect for a romantic getaway. Then we have yet another visit to the Osteria al Sole, which invariably appears in all three documentaries, and that really seems like a city institution not to be missed, if you happen to visit (can you believe that I’ve lived in Bologna for 29 years and I don’t recall ever setting foot in it?). The Sole’s unique characteristic (repeated every time) is that you only need to buy the drinks there (either beer or wine), while you can bring in your own food. That makes it unique, I suppose, but it also makes it the sort of place which is far more preferred by university students and – today – tourists, rather than natives (I will skip on the fact that Clive takes at least one selfie per episode – including one here – to send to his wife, which is understandably part of the drama, meant to draw you in, and almost inviting a subliminal intimacy between the place visited and the viewer – implying: “come here with your beloved other half for a great weekend away, and you’ll romantically experience together what I’m trying out alone”. As a ‘dramatic’ tool, I guess, this is also supposed to make the wife envious – however, within the context of the show, it also seems to say: “see how I constantly think of you when I’m away?”, and to promise: “we’ll be back here together” – and it works, as long as it fosters that identification: “I’m like anyone of you, and you could do this too”. At the end of the day, these ‘dramatic’ techniques – albeit simplified – go back to the roots of Greek theatre). And it’s all fine, don’t get me wrong – I understand this; there is a place for all these things, and they have a reason to be, but I simply wouldn’t go and look for them in Bologna. Maybe, this is the eternal, universal chasm between those who see the place from the outside, and those who know it from the inside, and who find it hard to understand how people could ever spend money to go there (unless their livelihood depended on it – so I can see why this would be different for someone involved in the ‘hospitality’ business. But there are also the natives who genuinely love the place, no doubt, and that have a less conflicted relationship with it than I).

The “Osteria al Sole” invariably seems to appear on any documentary featuring Bologna and its food tradition. This is a picture from the set of Rick Stein’s “long weekend” series.

What I find a bit more annoying is the omission of other things: Bologna is not an easy city to be, and I don’t think it’s ever been – not even in her ‘golden’ days. Even in other parts of Italy, I don’t think that people have a real idea of the place. But in my perception, Bologna has never been a “happy place”. Open-minded, maybe, but even that could be open to question. My mother (whom, I repeat, loves this place) has always called it “una città di bottegai”, which could more or less be translated as “a city of shopkeepers”, implying that people here have always been interested in money, trading, and in their little garden more than anything else. Traditionally, they used to milk students. And they still do – but now they also milk tourists. And because tourists are easier to milk, more profitable, and less trouble, students find no places to stay. In the university that prides itself to be the oldest in Europe, there has never really been a housing policy for students (there are a few studentati – I even had friends staying at one of them – but they are fewer than the number of students that enrol in an average year). And as for the university’s prestigious status, that would be another debatable issue, as being the ‘oldest’ doesn’t necessarily guarantee quality – there is an element of “sitting on the laurels” there, but that’s another issue altogether.

Be as it may, one of the city’s undoubted greatest prides – food – has greatly suffered as a result of tourism growing exponentially: entire streets have turned into a succession of tables where to enjoy “the dolce vita”, but Bologna’s great food tradition has been minimised and trivialised, as a result: as places multiplied, prices went up, and quality went down – it seems to be an almost invariable axiom. The few ‘real’ Bolognese people that still exist have started to avoid these places like the plague – much in the same way as Venetians carefully avoid St. Mark’s square. And as the city’s soul has been sold to tourists, authentic life has moved somewhere else: there are places where it still resists, but they need to be looked for at the margins – in districts such as the Bolognina and the Cirenaica, where tucked away in nondescript and once working class (now ‘multi-ethnic’) neighbourhoods are some remnants of those old osterie whose name I better not give away. Places where you can still order the notorious cotoletta Bolognese (a slab of meat, fried with ham and cheese, that defies the strongest stomach) or play the tarocchino Bolognese – one of the city’s oldest games. I gave you the name of the districts – so I challenge you to uncover those places on your own, if you’ve got spirit of adventure.

The “tarocchino Bolognese” is an old tradition in the city – it was in fact a divination system.

But Bologna never appeared to me as a particularly inclusive city, either; rather closed, actually. And mind you, I was born there – so, again, I should sing her glories. Instead, the place has always struck me as claustrophobic, like a big uterus (I remember real panic attacks, as a child, when they took me to the city centre – but fortunately we were living in a relatively more open location in the outskirts). When you walk under the ‘portici’ – the proverbial arcades – you barely ever see the sky: some people (the more devoted Bolognese) love them; others, like me, have never really taken to them, even though I can see their charme. As a compensation, when walking under them, now you breathe profusely an abundance of exhaust fumes: the arcades have turned into gas chambers, as they never managed to rid the centre of its traffic (despite talking about it since the 1970s – the issue goes back to the city being run by ‘shopkeepers’, I suppose). Also, unless you leave the centre, there’s barely any greenery – public, that is, as when you look at the city from above (the top of the Asinelli, say), there are in fact plenty of private gardens (fortunately, however, Bologna has hills, and its parks saved me as a child). And as I said already, the ‘stranger’ is not particularly welcome here, unless you can milk them. That’s the Bolognese psyche for you: but the topography of the place is so narrow that you cannot really expect it to be any different; people are invariably a reflection of the places they inhabit – despite this being, historically, a stronghold of the left (not so much, anymore).

Incidentally, I also remember the famous 1977 ‘movement’, made precisely by those students who had come from all over Italy to the university in Bologna, and which was partly suffocated in an urban guerilla of which I still retain a memory (as I found myself in it – age 7). Unlike now, those were highly politicised times, but all those people had nothing to do with Bologna. It was more a clash between the establishment and those who wanted change, and Bologna (just like many other cities at that time) happened to be a stage for it. I remember there were two streams running in parallel: the Bologna of the Bolognese, and the Bologna of the ‘outsiders’ (namely, students), and I don’t think that these two worlds really touched, if not tangentially: the city of the ‘osterie’ was perhaps the only thing that they had in common, then. Places like the Osteria Biassanot (literally, “Chew-the-night”) or Orfeo, and other suchlike, were probably frequented by both. While the bourgeois restaurants – such as the Cantunzéin, situated right at the heart of the university area – were carefully avoided by the students; eventually, they would be raided and destroyed with acts of violence that also wanted to be a statement of sorts. Anyway, nothing of all that, now – so there’s nothing to fear: today no-one even remembers the ‘77 movement. In fact, truth to be told, these events were evoked in the RAI documentary I mentioned above, with some poignant repertoire images that, for a minute, made me authentically nostalgic. As I miss those times – if anything, as I miss my childhood, and I miss my grandparents: how could I not? But today, what’s left of all that? Barely anything. And I bet that the average English or American tourist hasn’t got the faintest idea about all this, as nobody tells them. And why would they? Well, I would. If you are really interested in getting to know a place, you would want to know its history – especially the most recent one – and you would want to know its shadow side, too – or at least get a glimpse of it. It’s not by chance, I believe, that so many noirs and dark stories are set in “the happiest city”. If I were a tourist visiting (provided that I feel very much like a tourist now, on the very rare occasions when I go back), I certainly would want to know that Bologna is not just tortellini and towers.

Above: the ‘sfogline’ (pasta makers) are another institution in Bologna; here they are pictured with Rick Stein on the set for the “long weekend” series.

Below: the entrance to the ‘sfogline’ shop features, inevitably, also in the Bologna episode of “Clive Myrie’s Italian Road Trip” series.

And that’s where my work could come in. If only I could make documentaries (in English) to convey the real spirit of a place, and not just what wants to be sold – with compliant local people telling you how beautiful life is there, and how ‘happy’ they are. I remember a massive shadow side to Bologna, which ultimately I see no point in concealing, if one is really interested in knowing the place. But I certainly wouldn’t want to make documentaries only on Bologna – there are so many other places whose story I’d love to tell (like I already do in writing)! Still, chapeau to the BBC (and the CNN) for making these documentaries, as with all the omissions and the glossing, they still bring something of the place home – to the native and the visitor alike.

Check out Clive Myrie’s Bologna episode at the link below:

“Clive Myrie’s Italian Road Trip, Series 1: 12. Bologna” is visible (from the UK) at the following link: www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p0fds1sv via @bbciplayer

© Max Calligola 2024

A Canadian, I spent two months in Bologna “tre anni fa” learning some basic Italian, and writing a book. My choice was pragmatic - access to a good train connection for weekend getaways and modest school and lodging costs.

My wife and I fell in love there again. Our experience was, obviously, limited and certainly somewhat idyllic, especially following trips in the past to Rome and Venice. And - to be sure - on our return a year later, it was a little less rose-colored - but, still, there are marked differences between Bologna and tourist rich areas like Rome, Venice, Florence, Cinque Terre, and others where mass produced tourist goods and tourists themselves are everywhere.

Partly, I think, because other than Asinelli Tower (which is now closed to tourists) there really are very few iconic “Instagram Photo Ops” in Bologna. No Trevi fountain, no Ponte Vecchio, no spectacle like Piazza San Marco and the Ponte Rialto in Venice. The Basilica di San Petronio in Piazza Maggiore isn’t even completed… the façade remaining unfinished with a rather rough-hewn look.

Bologna is not a place your Facebook friends will fawn over. Which is why, I think, it’s a great place to hangout and just, ‘be’. Which is why, I hope, it will never become a tourist mecca or a place where grifters seeking to take advantage of tourists will gravitate to like they do in the “must see” areas of Italy.

Last year - seeking a similar experience - we visited Padova, and were similarly pleased with that experience, and return again this May.

I think I get your point, and speaking with my Italian teachers I did get a sense of the struggle for locals that tourists don’t see… low wages, higher costs, lack of housing… how government inefficiency is the biggest pandemic, as bad as COVID was… and grass is always greener… but, Bologna, for me will always resonate in ways far beyond a climb up Asinelli or a charcuterie board at Simoni.

I would love to see deeper and less facile documentaries on Italy and it’s innumerable special places… please do that!

Btw… for less a typical Bologna documentary - maybe you’ve seen this…?

https://youtu.be/iFVv65Adwis?si=X3koNDfO49eg8D9S

Grazie mille!